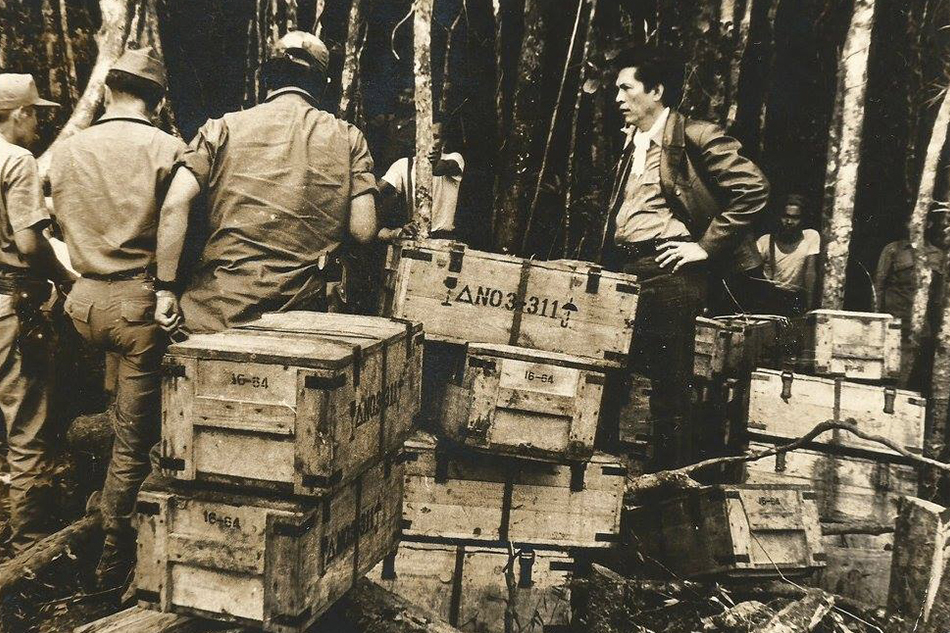

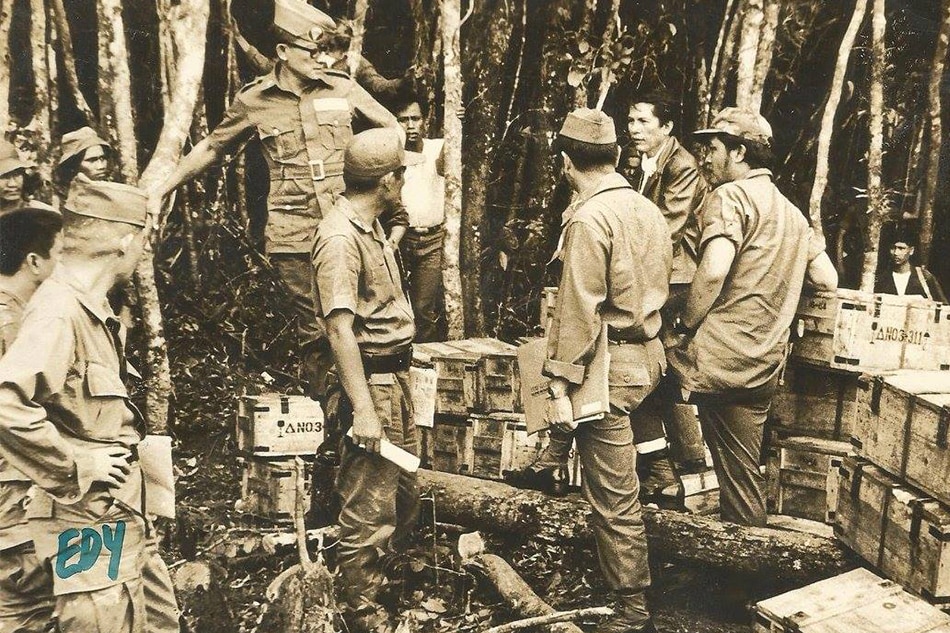

Juan Ponce Enrile surveys the intercepted arms landing—a haul that included automatic rifles, ammunition, bazookas, mortars, and anti-aircraft guns. Photograph from Francis Karem Elazegui Neri NPA fighters trekked through the Sierra Madre to Digoyo Point in Isabela where a grand arms landing was about to take place from aboard the MV Karagatan. Out of seeming nowhere, the Philippine military arrive to intercept their efforts. Rolando Peña writes about what happens next.

Editor’s Note:

Throughout the 70s, Communist Party of the Philippines chairman Jose Maria Sison sent several delegations to Beijing with an armaments shopping list that he would present to Chinese officials. According to military reports, Sison’s emissaries negotiated for armaments in the form of M-16 automatic rifles, ammunition, and heavy weapons, and China supplied about 1,200 M-14 rifles, bazookas, mortars, communication equipment and medical kits, according to military reports.

After China refused the CPP-NPA request for a submarine, Fidel Agcaoili, Sison’s personal emissary, traveled to Japan and purchased the Kishi Maru, a 91-ton, 90-foot steel hulled old fishing trawler. China agreed to pay for the boat, which was later christened the MV Karagatan, the military added.

The M/V Karagatan successfully loaded armaments from Fukien province. By the end of June 1972, the vessel sailed to the Philippines to drop off the arms at Digoyo point in Palanan, Isabela. Members of the Philippine military were able to intercept the unloading of arms through reconnaissance aircrafts that baited the old trawler, leading it to its eventual breakdown. In the following days, the military and NPA fired at each other from the shores of Digoyo. As the military was strengthened by coordinated air and naval gunfire, members of the NPA escaped to Quirino province through the thick and rugged jungle terrain of the Sierra Madre.

Below is a log of the events penned by Rolando Peña, the renowned geologist and left-wing revolutionary who steered the M/V Karagatan, and escaped military gunfire with his comrades.

Peña’s account was read at a parangal held by the NIGS (National Institute of Geological Sciences) witnessed by writer Barbara Mae Naredo Dacanay. Peña passed away last November 2018.

Dates included below were not in Peña’s original account but were added as a guide by Dacanay.

Silhouettes of fishermen going out to sea dissolved in the darkened Batangas Bay as our twenty-foot (or so) wooden-hulled boat gunned the engine towards where the sun disappeared. The five New People’s Army fighters and I huddled against the cold breeze that night in May 1972 as we skirted the coastline of Cavite, then steered away so as not to be noticed by the basnigs, the brightly-lit heavy fishing boats off Bataan.

When I agreed to guide the wooden hulled boat to Isabela on the eastern Pacific Coast of Luzon Island, to deliver rice and field supplies, I explained that I could bring the boat from one point to another as I could get my bearings from landforms as reference points.

We took turns at the helm, but we were so focused on maintaining our direction that we failed to check our actual surroundings. As we swung along the coast of Zambales, our hull struck a rock and we began to take in water. Fortunately, we had a manual pump in the boat, and we took turns at it until we reached an isolated beach in Aparri, where we were able to take a look at the damage. Indeed, there was a gash that two lengths of my palm could not cover. So we went on our way, taking turns at the pump.

After rounding Port Irene on the northeast nose of Luzon, we hoisted the sail as there was a tailwind that made us skim the water faster. We did not encounter any coast guard patrol as we came abreast of Divilacan Point on the coast of Isabela for a rendezvous with the NPA.

However, the coastal water was strewn with rocks so we (the NPAs aboard the boat) went back a few miles and met them (land-based NPA) at the mouth of Digoyo River. Hardy faces beamed in welcome as we came ashore to handshakes and backslaps for a mission well done. Lieutenant Victor Corpus (then a military officer who had just defected to the NPA) feted us with a hearty meal of boiled fresh-water fish, river shrimps, and rice on a long banana frond. Not long afterwards, a steel hulled fishing boat, the MV Karagatan (which carried 1,400 AK-14 firearms from Fukien) anchored very near the coast and unloaded more supplies.

We were to about to bid the crew of the M/V Karagatan goodbye when I was handed a a small strip of paper from Joma Sison. It was a letter from the Communist Party Chair. The hurried scribble gave me the task to help navigate the M/V Karagatan across the South China Sea, from the Pacific Ocean on the eastern seaboard to northwestern seaboard of the Philippines to reach China. We were to fetch supplies and weapons and bring them back to the Philippines for a second arms landing. Sison was impressed by stories that I could sail by the stars—something called celestial navigation. What he did not realize was that stars, for me, were only for viewing, not for seeking guidance.

You’ll never truly appreciate the vast sky until you see it almost filled with stars lighting the endless sea.

Those of us aboard the bancas landed at our destination in Digoyo River and received our load of supplies: firearms, and ammunition from MV Karagatan for the men of Lt. Corpus in the Sierra Madre. We laid at anchor for two days to let a storm pass before setting off on an easterly bearing toward Luzon. Midway, we sprang a leak perhaps because we were fully loaded—but there was no question of turning back as we were in the middle of our journey. One of the crew members found the source of the leak and remedied the problem, so we were able to proceed with an easier mind frame.

July 4, 1972

We reached our rendezvous deep in the night. There was no response to our signals to the shore. As morning broke on July 4, 1972, I and a couple of comrades lowered a dinghy, took a box of rifles and then rowed to shore. It was then that members of the NPA emerged from a thick foliage. One of the men shouted my name, recognizing me as our boat approached because of my long hair. There was much shouting in jubilation and hugging. But only for a while. Our merchandise was a real heavy shipment. How could we unload it in the quickest time?

We started unloading our cargo by transferring them to several bancas. It was a tedious process, and at one point some cargo fell into the water. Then, from out of nowhere, a small plane appeared, passed, and then circled towards us. I thought that we had been spotted by the military. So I decided to sail our small ship right up to the mouth of Digoyo River where comrades were able to reach up to get our cargo. We finished unloading just before sunset. As we huddled for farewells, a T-34 Mentor plane buzzed through the treetops.

We hurried to get out of the place. I told the co-captain of the M/V Karagatan that we should not turn on the engine because the propeller might hit a rock. We could just let the ebbing tide current take us out of the river. But he was impatient.

True enough, we hit a rock that damaged the hydraulic system and we could only move in circles.

Eventually, we were able to maneuver offshore, the engine guy was able to identify the trouble. He said he needed a little time to do some welding. In the meantime, the captain of the M/V Karagatan turned on the radar and saw something moving towards us. It kept getting closer, but we could not see what it really was. It was not using any light.

The captain ordered us to abandon ship. There was a scramble for life vests and everybody started jumping overboard. I could not find a life vest, but there was a guy in the water who was shouting for help because he did not know how to swim. I jumped into the water and came up to him. I told him to relax and let me share his life vest and I will bring us to the shore.

As we made our way to the beach, the people in the unidentified vessel came up to our ship (MV Karagatan), switched on searchlights and started asking who we were through a megaphone. “What are we doing here? Come out!” (we were ordered). But we had already reached the beach where Corpus’ men had positioned themselves behind trees and rocks to take action. Further in the woods, we had supper and then we found some comfortable spots for a night’s rest.

July 5, 1972

The following day, I asked Lt. Corpus to let us go on our journey back to Manila since our part of the mission had been accomplished. The ship’s captain, a veteran of the Hukbalahap rebellion and I hit a faint forest trail behind a Dumagat guide in the late afternoon. An hour into our trek, we heard a barrage of rifle fire. A few Dumagat families came scampering hither and thither for it seemed there was a battle going on.

July 6, 1972

We plodded on, sleeping where darkness would overtake us, and moving on the next day. One time, we slept under a tree while it was raining, but we got drenched anyway. Our Dumagat guide was really savvy. One time, he said that a wild boar just passed by, and asked us to wait. After a short while, he was back with a wild boar, which he shot with one of the new rifles that we had brought across the sea. We had consumed our two-week supply of rice just on the sixth day because we shared it with Dumagats whom we met along the way. We finally crossed the Sierra Madre and came upon comrades who were setting up relay camps along a river for the couriers of our arms shipment. We spent the night at the base camp in the forest of Isabela where temporary quarters for around 25 persons had been set up.

We moved on the next afternoon with a plan to be joined by armed escorts farther down the hills. When we reached a barrio, we were told that our supposed escorts had left because there was some troop movement in the area. We were advised to cross the river and hide in a hut atop a hill overlooking the barrio. We had a peaceful night.

July 8, 1972

In the morning, while waiting for our breakfast to be brought to us, our female companions pointed to a couple of jet planes at a distance. Our experienced Huk veterans shouted for everybody to hide behind some huge rocks nearby. Within seconds, the plane circled overhead and strafed the hut with machine gunfire and rockets. The hut did not even suffer a direct hit. When the planes had left, we fled to the forest and crossed the river about a kilometer away, where we heard troops firing as they crossed the river from the barrio to get to the hut where we stayed overnight. We rested at a farm plot but then heard firing nearby so we went inside the first again. A farmer who was passing by told us that the soldiers had occupied their barrio and were firing in the air to scare people.

July 9-11, 1972

We stayed beside a creek for two days. Planes were bombing possible NPA campsites in the forest and it seemed there was a small war going on. On the third day (July11, 1972), we were told that the barrio folks were advised to evacuate as the T-34 Mentor plane was going to bomb the area. True enough, the barrio was completely deserted when we came in the late afternoon. We passed the night in a small creek choked with wild bananas called saging ng matsing. They bore small fruits with pepper-sized seeds—so you could hardly eat the flesh, but they were sweet. And they were supper for the night.

July 12, 1972

We moved only during the evening on the following day and found some comrades with the barrio folk in a field. We were given biscuits and soon entered a barrio that seemed safe.

July 12-19; 26, Aug 2 and 9

We spent some weeks sneaking from one barrio to another, inching towards the flatlands. We always travelled by night—no one talked and no lights were allowed along the way. At one point, we had to cross a field of makahiya, and, being barefoot, it really hurt and my soles were all bloodied. There were even trees and bushes with long claw-like thorns that tore into your skin when you brushed against them.

Aug 9-30 (intermittently, over four weeks)

Finally after a few weeks of dodging the army, trekking from one barrio or camp to another, we reached an NPA camp near the national highway in Tumauini, Isabela, We were given a change of clothes, waited for a bus in a safe house along the highway. The bus we rode on carried some wounded soldiers.

The rains had been going on the whole of July and August in 1972. In Nueva Vizcaya, we joined a train of vehicles at the Dalton Pass that couldn’t move because of landslides triggered by the unrelenting rains. A child with the mother waiting for the traffic to ease died because they had been there for a couple of days with nothing to eat and the villagers nearby were charging a lot for the food they were selling. Trucks laden with bananas began to smell as the over-ripened fruits began to ferment. We walked over five kilometers down mountain road to get to the other end of the traffic. And then we finally reached Metro Manila.

President Marcos thought that the NPA, now equipped with new weapons from China, posed a serious challenge to the government. Partly on account of this, he decided to declare martial law in September.

The weapons we delivered were the first batch of armaments. There was another batch or two to be picked up. But that is another story.

The story Karagatan, by Rolando Pena was published in “Ordinary Heroes and Discovered Icons of the UP High Class ’57”

Photographs from Francis Karem Elazegui Neri

Source and Original Article:>>> ANC X

Comments